Five Boats That Define the English (And One That Now Challenges It) Pt 3/3

01-06-02

“A society that has lost its sense of limits has lost its sense of itself”

The smallest boat, carrying the heaviest question

6. The Rubber Dinghy: A Fractured Mirror

HMS Victory sailed at the height of Britain’s confidence, when the nation faced outward and the world came into view through a spyglass. Today the world comes to us in rubber dinghies. Small, fragile, anonymous. And somehow these soft-sided boats unsettle us far more than any foreign navy ever did, because they force us to confront not what Britain once was, but what Britain is now.

They don’t define the British character so much as expose the fracture running through it. A cheap inflatable crammed with migrants, powered by an underpowered outboard, creating a political earthquake no government seems able to steady.

A cheap inflatable crammed with migrants is creating a political earthquake no government seems able to steady.

The dinghies themselves are factory-made inflatables: flimsy knock-offs of leisure boats, overloaded with people and shoved into the Channel by smugglers who vanish before the carburettor even has time to flood. No history. No glory. No teak, no brass, no chartroom. And yet they may be the most important boats of all. Not because of what they are, but because of what they force the English to confront.

On board is a mix of refugees fleeing war, dictatorship and persecution, but overwhelmingly young men seeking work and opportunity. Almost all depart from the French coast, not because France is unsafe, but because the UK is seen, rightly or wrongly, as a place where English is spoken, black-market jobs are plentiful, and asylum outcomes appear more favourable.

On board is a mix of refugees fleeing war, dictatorship and persecution, but overwhelmingly young men seeking work and opportunity.

And they carry something else too: the anger of working-class Britons, who see the NHS collapsing, housing scarce, schools bursting, wages flatlining. Mothers worried about daughters walking home. Women altering routes to avoid certain areas. These anxieties are too easily dismissed as ignorance or bigotry, often by people who live far from the towns and estates absorbing the pressure, which makes working-class Britons feel, again, rightly or wrongly, that they are being lectured by a new ruling caste.

Not the old aristocracy (who they’ve never listened to anyway), but the modern lawyer-media class: people who live nowhere near the problem, suffer none of the practical consequences, yet still use television studios and opinion columns to announce that everyone else must be kind, patient and terribly understanding. It isn’t cruelty that fuels the resentment, it’s the suspicion that they’re being told to swallow the sauerkraut while others sermonise from the pulpit with a full plate.

Working class feel NHS collapsing, housing scarce, schools bursting. Parents worry about daughters and feel lectured by a new ruling caste

This tiny, fragile craft challenges everything the others embodied: our instinct for fair play, our pride in humanitarian rescue, our belief in secure borders, and our long-standing certainty about who “we” are.

We don’t know whether to extend a hand or guard the line. We don’t know whether our compassion is being exploited, or whether fear - fear of losing control, of losing identity, of losing the Britain we thought we knew - is quietly distorting the values we claim to defend. The rubber dinghy forces the question: what does Britain owe, to whom, and for how long?

For a nation raised on queueing, queue-jumping is the ultimate sin. For a nation raised on helping your neighbour, letting people drown is unthinkable. And so Britain finds itself torn between two instincts that once coexisted comfortably but now collide head-on in the cold chop of the Channel.

Irenka volunteered for the RNLI - vanishing into storms at midnight to save strangers then be back making the kids’ breakfast by morning.

During our years on the south coast, Irenka volunteered for the RNLI. She’d vanish into a storm at midnight to save strangers, then be back making the kids’ breakfast as though nothing unusual had happened. Ordinary heroism, the quiet kind Britain excels at.

The RNLI, once one of the most universally respected institutions in the country, now finds itself dragged into the political firing line. Volunteers, unpaid, unarmed, undeserving of the vitriol, are accused of being a “taxi service” for people who deliberately put themselves in danger, rely on the charity of strangers and then expect to be housed and fed on arrival. The crews didn’t cause this. Politics did.

Endeavour showed ambition. Beagle showed curiosity. Black Joke showed conscience. Endurance showed resilience. Victory showed confidence. And the rubber dinghy? It shows British values in a state of confusion. Outflanked by a globalised world, like an ageing lion still expected to protect others when it can barely protect itself.

Five boats - Endeavour, Beagle, Black Joke, Endurance, and Victory - five moments, five versions of Britain staring back at itself.

At the beginning of this essay I suggested Britain’s real story isn’t written on land at all. It’s written in wood, iron and canvas; in courage, stubbornness and sheer bloody-minded will. But perhaps it IS also written in the soil. In the quiet graft that keeps our garden of England alive.

I live in Rottingdean, home to the Rudyard Kipling Gardens, a place closely associated with the man who wrote The Glory of the Garden. I walk through them often and see the daily labour. The pruning, raking, weeding, winter patching. Everything that keeps it alive. Because every ship in this tale, from Endeavour to Black Joke to the lifeboats pounding through the Channel, was steered not by mythic heroes but by ordinary people doing exactly that: the hard, unglamorous work that keeps the whole thing afloat.

Britain endures not through myth, but by ordinary people doing hard, unglamorous work that keeps the whole thing afloat.

Kipling put it perfectly: “Our England is a garden, and such gardens are not made by singing ‘Oh, how beautiful!’ and sitting in the shade.” That line sums up Cook’s rise from farm labourer’s son to master navigator. It sums up Shackleton’s fight against impossible seas. It sums up every sailor who ever earned their place through competence, grit and contribution.

And it’s why the debate over those dinghies hurts as much as it does. Because the British, at heart, still believe in the rules of the garden, and that everyone pulls their weight. That everyone earns their place, and nothing worth harvesting comes without generations of hard graft, not shortcuts. Our conflict between compassion, empathy and fair play is what truly tears us apart.

The British, at heart, still believe in everyone pulling their weight. A conflict between compassion, empathy and fair play.

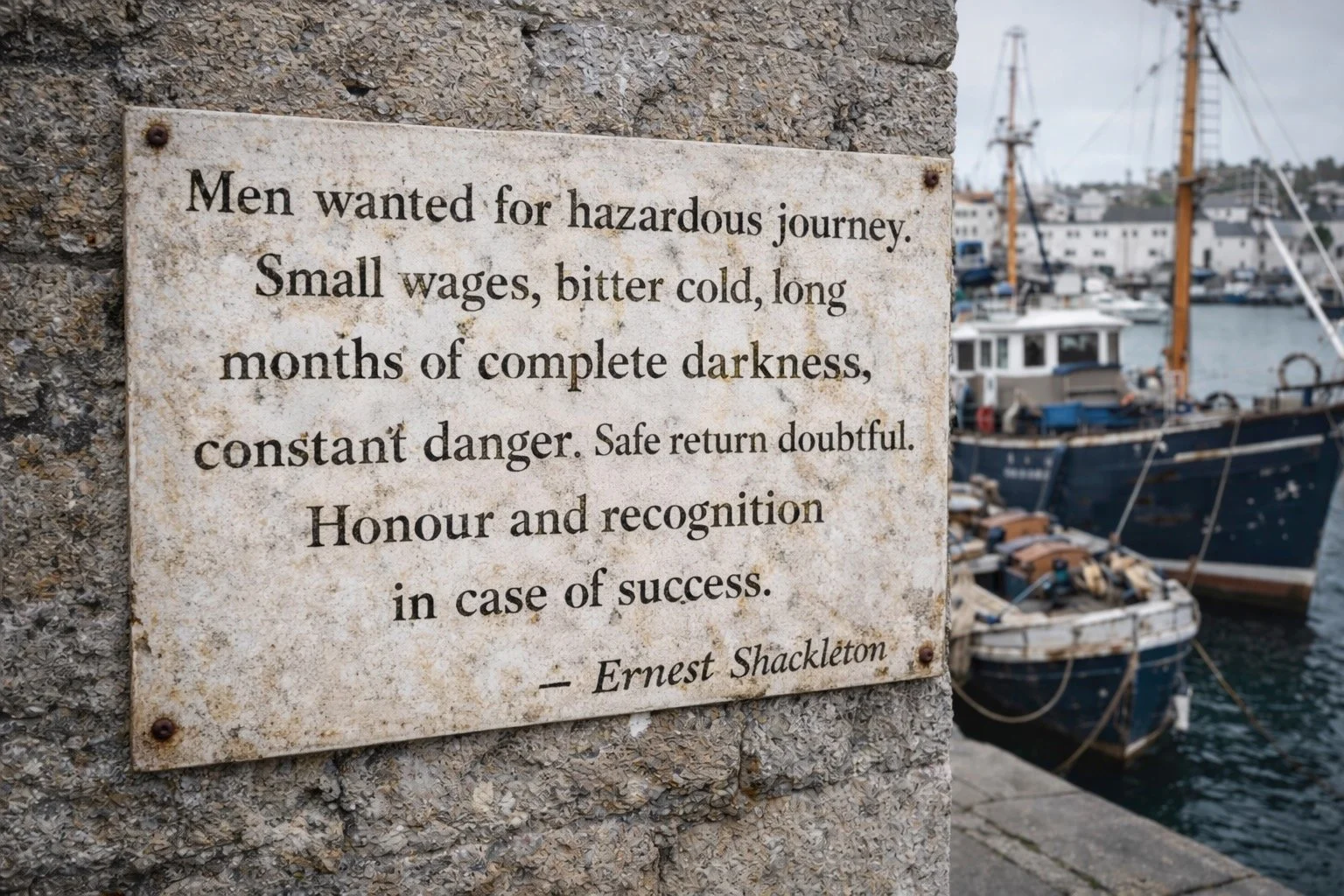

And sooner or later, modern Britain will have to decide which of its values are still watertight, and which are sinking the boat. Change is always hard, and tough decisions will have to be made by strong leaders. As Shackleton’s legendary advert put it:

“Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.”

A job advert for the past, perhaps, but also a question mark hanging over our future. And after sailing around the world myself, I suspect Britain will meet whatever’s coming not with slick precision but in the usual, endearingly chaotic fashion: mildly underprepared, quietly optimistic, and determined to keep a hand on the tiller long after common sense has checked out.

Men wanted for hazardous journey. A century-old warning still echoes uncomfortably into the present.

If history tells us anything, we’ll shove off in the wrong boat, with half the kit missing and the tide squarely against us. Yet somewhere between the muttering, the swearing and sticking the kettle on, we’ll do what the British have always done best.

Keep buggering on.

If you want more straight-talking tales from life afloat, and opinions on British Naval history and boats that define the English like the migrant dinghies, then you’ll love our upcoming book. We're inviting early readers to join the pre-launch crew and get behind-the-scenes access as we wrestle it into shape. It’s honest, unfiltered, and occasionally useful. Sign up here to get involved, give feedback, and be part of something that’ll either be a bestseller or a brilliant cautionary tale.