Five Boats That Define the English (And One That Now Challenges It) Pt 2/3

01-06-02

“The greater the obstacle, the more glory in overcoming it”

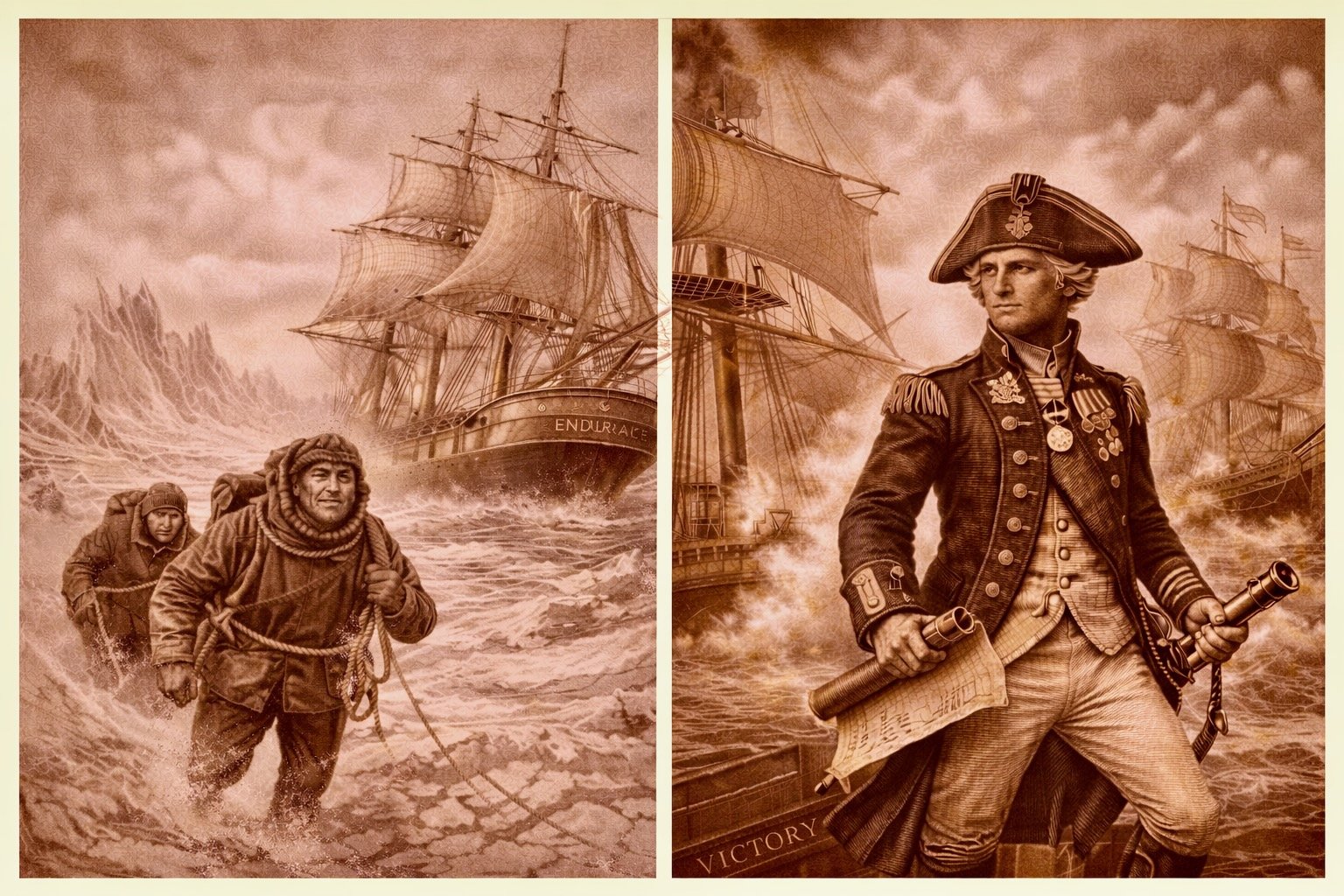

Shackleton / Endurance, Nelson / Victory. Endurance made failure heroic and Victory made success myth.

In Part One we met Cook’s Endeavour, Darwin’s Beagle and Downes’s Black Joke: working boats that quietly reshaped maps, minds and morals through competence, curiosity and conscience. In Part Two we move on to two very different ships and two very different lessons. Shackleton’s Endurance shows what English leadership looks like when everything goes wrong. Nelson’s Victory shows what happens when confidence, audacity and firepower all align. One was crushed by ice, the other by history. Both became myths. And both tell us as much about who the English think they are as what they actually achieved.

4. Endurance: Courage Meets Futility.. and Refuses to Quit

Sir Ernest Shackleton stands on Antarctic sea ice beside the trapped expedition ship Endurance

After the Black Joke, you’d think the English would cling proudly to a rare example of unambiguous, moral success: a ship (or in this case an entire squadron) that actually did what it set out to do, thrashed the slavers, saved lives, and came home with its timbers roughly intact.

But no.

The English react to moral grandstanding with all the grace of a cat facing a cucumber. We are far more comfortable with failure and self-deprecation.

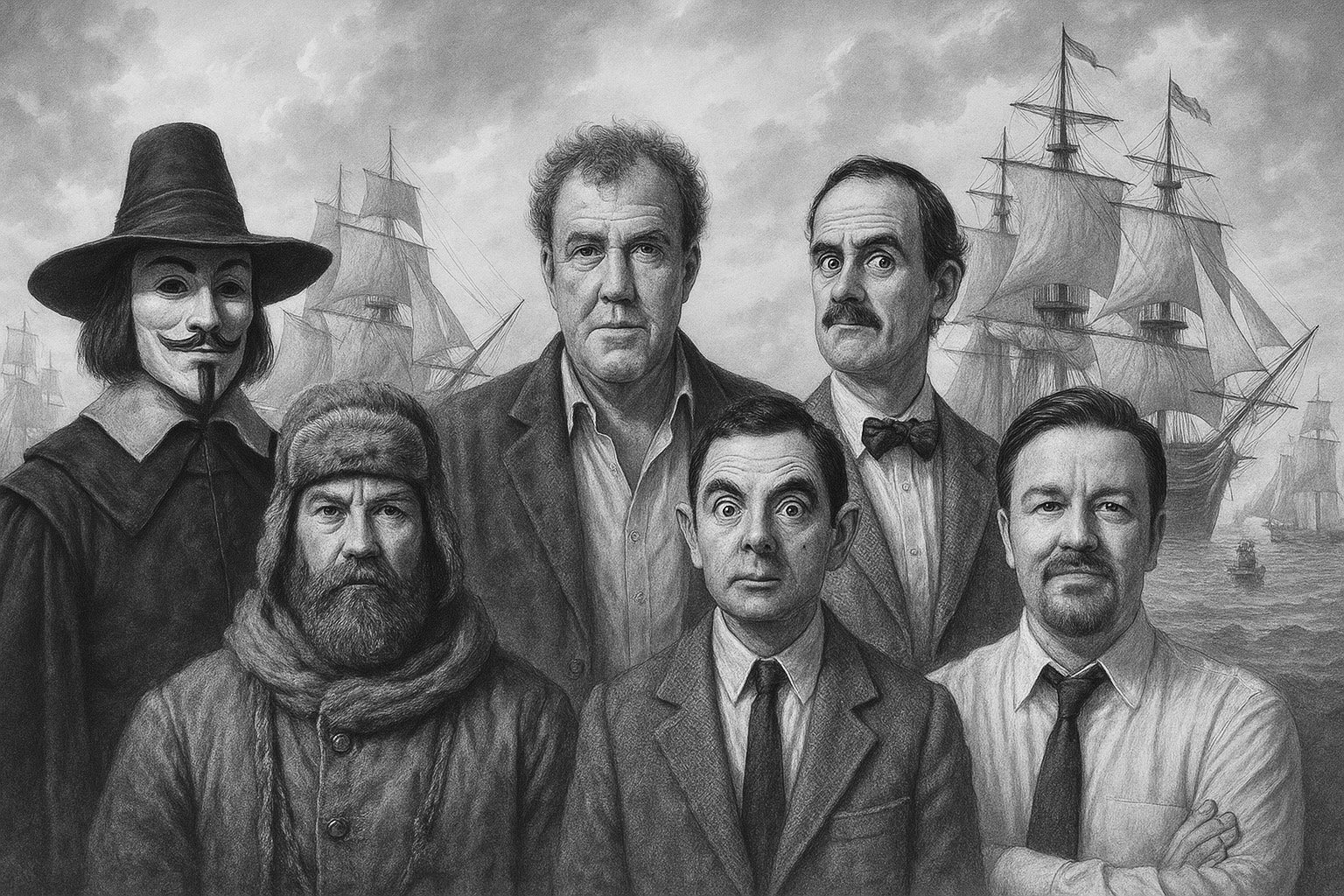

So instead of celebrating the unsung heroes of the West Africa Squadron, we fixate on the folks who charge headlong into disaster and somehow turn it into a career highlight. Success slips quietly into the footnotes, but failure (provided it’s dramatic enough) isn’t just forgiven in England; it’s practically a national sport. Think Guy Fawkes, Scott of the Antarctic, Jeremy Clarkson or fictional archetypes like Basil Fawlty, Mr Bean or David Brent.

These are the people we turn into myths and legends, because nothing tickles the English quite like a heroic face-plant executed with total conviction. Failure, done with enough enthusiasm, somehow becomes the most English achievement of all.

People we turn into myths and legends, because nothing tickles the English quite like a heroic face-plant executed with total conviction

And standing at the top of this strange national altar is Ernest Shackleton, the man who proved that if you’re going to fail, at least fail heroically, photogenically, and with enough grit to make future generations develop inferiority complexes.

I didn’t fully appreciate the scale of these polar obsessions until I wandered through Mawson’s Hut in Tasmania and later the Subantarctic Plant House in Hobart. A chilly little greenhouse that somehow makes Antarctica feel both impossibly remote and uncomfortably real. It’s one thing reading about these men; it’s another thing stepping into a room designed to imitate the climate that nearly killed them.

Endurance slipped beneath the ice leaving 28 men on buckling ice floes in sub-zero temperatures with no hope of rescue

The plan itself was simple enough in that wonderfully overconfident Edwardian way: sail to Antarctica and march clear across the continent as if it were a brisk winter stroll. His ship, Endurance, was a purpose-built polar brute and massively over-engineered. One of the strongest wooden vessels ever constructed.

Which makes it all the more impressive, and slightly horrifying, that the Weddell Sea simply grabbed her and crushed her like a beer can. When Endurance slipped beneath the ice, it left all 28 men standing on buckling floes in sub-zero temperatures with no ship, no shelter, and no hope of rescue.

Shackleton knew that salvation wasn’t coming. Staying meant dying. Marching across drifting, cracking ice was futile

Weeks of freezing and listening to the ice groan beneath their camp convinced Shackleton that salvation wasn’t coming. Staying meant dying. Marching across drifting, cracking ice was futile. Ahead of him lay only degrees of impossibility.

So he selected the three lifeboats and ordered the men into seven days of freezing spray, grinding seas, hunger, exhaustion and constant bailing before they collapsed onto a bleak scrap of rock called Elephant Island.

Shackleton selected 3 lifeboats and ordered the men into 7 days of freezing spray, grinding seas, hunger, exhaustion and constant bailing

Everyone remembers Endurance, but the real hero of the whole escapade was the James Caird, a wooden lifeboat remodelled by ship’s carpenter Harry McNish using scraps of timber and seal blood. Shackleton loaded her with three weeks of food, a bit of rope, and the hopes of the entire expedition.

She set off with six men into the most vindictive ocean on earth. Shackleton chose his best navigator and carpenter for the crossing, but he also took the most cantankerous troublemakers, rather than leave them behind to sabotage morale.

The Southern Ocean responded as it always does to small boats: by trying to kill them immediately. Sixteen days of breaking seas, sleet, and wind that shrieked like a banshee. The men bailed constantly, slept curled in the bilges, and relied on Worsley snatching celestial sights through momentary gaps in the cloud and hammering them into a fix by spherical trigonometry in a rolling boat. A task which, today, would probably prompt a formal complaint from a child asked to do long division in a warm kitchen.

The real hero of the escapade was the James Caird, a wooden lifeboat remodelled by ship’s carpenter Harry McNish

After sixteen days of rolling apocalypse, the James Caird staggered into the lee of South Georgia. Their clothes were frozen into rigid shells, their faces cracked, their hands clawed from hauling sodden lines. And yet, it still wasn’t over.

They had landed on the wrong side of the island, forcing Shackleton, Crean and Worsley to slog for thirty-six hours over unmapped mountains and glaciers in little more than soaking rags and stubbornness. When they finally lurched into the whaling station at Stromness, the Norwegians could barely believe they were human.

They had landed on the wrong side of the island, forcing them to slog for thirty-six hours over unmapped mountains and glaciers

But Shackleton didn’t stop. He cleaned himself up, turned straight around and spent months fighting sea ice and weather in repeated rescue attempts until, at last, he reached Elephant Island and lifted the remainder of his men off their rock. Not one of them had died. In the long ledger of English heroic failures, Shackleton’s catastrophe somehow became an impossible triumph.

If Cook revealed what England could do with opportunity and grit, and Darwin revealed what it could do with opportunity and curiosity, then Shackleton revealed what it could do with a leadership mentality so stubborn it practically bent the laws of nature.

5. Victory: Myth, Swagger and Delusion

Victory wasn’t just a ship, she was the battering ram that turned the Royal Navy into the most dominant maritime force on earth.

If Shackleton personifies heroic failure, then Nelson personifies heroic overachievement. The man who won so often and so noisily that England has spent two centuries trying to decide whether to treat him as a national treasure or an irritating elderly relative who spoils Christmas by constantly reminds everyone how disappointed he is in them.

Nelson reshaped naval warfare by sheer force of nerve, rewriting the rules of engagement and handing Britain a run of victories so decisive they locked down the world’s oceans for a generation. He smashed French and Spanish fleets, kept Napoleon bottled up, perfected break-the-line tactics, and turned the Royal Navy into the most dominant maritime force on earth.

Nelson reshaped naval warfare by sheer force of nerve, inspiring his men through sheer charisma and complete disregard for his own safety.

By Trafalgar he’d lost an eye, an arm, and developed a healthy respect for French cannonballs. But remained the living embodiment of British sea power, inspiring his men through sheer charisma and complete disregard for his own safety.

Nothing wins the English heart like a man who can chase enemy fleets across oceans and then, with equal enthusiasm, chase other people’s wives across Europe. His love-life had all the decorum of a Bridgerton subplot, and nothing titillates the English quite like a national sex scandal.

Nelson’s love-life had all the decorum of a Bridgerton subplot, and nothing titillates the English quite like a national sex scandal.

Victory wasn’t just a ship; she was the battering ram that smashed Napoleon’s naval ambitions, the floating HQ of Britain’s greatest maritime gambler, the wooden sledgehammer that secured a century of swagger. Although Victory survived Trafalgar, Nelson did not. His body was preserved in a vat of brandy and lay briefly in Gibraltar while Victory patched herself up.

We visited Gibraltar during our circumnavigation, partly for fuel, partly for paperwork, and partly because, like any good English sailor, I wanted to see where Nelson paused on his final journey home. There’s something very English about winning a decisive battle, dying dramatically, and then travelling back to London pickled like a Regency rum truffle.

Victory wasn’t just a ship; she was a battering ram. The wooden sledgehammer that secured a century of swagger on the sea

Victory didn’t retire after Trafalgar; she simply changed jobs. Like an ageing rock star, with less touring and more personal appearances. She’s technically still in the Royal Navy today, making her the oldest warship in the world still in commission. She has served longer than the United States has existed, which tells you everything about the ship and rather a lot about Britain.

Once the sharp end of global power, she is now a creaking relic held together by scaffolding, sentiment and life-support technology. Perhaps a quiet warning to younger maritime powers about how these stories tend to end.

Victory now sits in Portsmouth like a royal relative quietly parked in a care home, enduring the indignity of being selfied by tourists

This great ship of our past, once the thunderous pride of the nation, now sits in Portsmouth like a royal relative quietly parked in a care home, sipping tea and enduring the indignity of being ogled by tourists snapping selfies on their iPhones, drifting between the café and the gift shop, pausing only long enough to ask what that strange smell is. She has become the perfect symbol of the English nation’s slow shuffle from imperial swagger to politely managed decline.

And sometimes I wonder what Nelson makes of his afterlife in Trafalgar Square. Perched on his column like a slightly battered action figure, he looks down on a Britain that now fills the plinths beneath him with giant blue chickens, squashed bronze thumbs and whatever the Tate Modern has barfed up that month. The man who once rearranged the French and Spanish navies for fun now surveys a nation obsessed with cancel culture, safe spaces and men in dresses. You can almost picture him squinting across the square, trying to work out what exactly the country and empire he fought for has turned into.

I wonder what Nelson makes things now, perched on his column squinting across the square, trying to work out what happened to the nation.

And yet, for all the modern noise, Nelson and Victory still define something deep in the English psyche: pomp and ceremony, courage without caution, and the unshakeable belief that a creaking old institution held together by string and optimism will somehow carry us through.

If you want more straight-talking tales from life afloat, and opinions on British Naval history and boats that define the English like the Endeavour and HMS Victory, then you’ll love our upcoming book. We're inviting early readers to join the pre-launch crew and get behind-the-scenes access as we wrestle it into shape. It’s honest, unfiltered, and occasionally useful. Sign up here to get involved, give feedback, and be part of something that’ll either be a bestseller or a brilliant cautionary tale.