Sailboat Systems and Things That Break

01-04-09

“The difference between a sailor and a passenger is, you must learn to love salt water, fear no storm, and fix everything yourself.”

Woody fixing boats in exotic locations - here mending a generator hose in Cairns, Australia.

DON’T PANIC!

Let’s be honest, we could fill an entire book on boat systems and maintenance alone. But luckily we don’t need to, because Nigel Calder already wrote the classic, Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual.

However, as Mark Twain (allegedly) said, “A classic is a book which people praise and don’t read.” And to be fair, you'd struggle to stay awake past Efficient and Cost-Effective Electrical Systems for Energy-Intensive Boats.

Are you still with me?

Still, Calder’s indispensable tome is found propping up engine hatches or absorbing coffee spills in panic-stricken cockpits the world over. It’s widely regarded as the definitive survival guide for anyone mad enough to go to sea with wires, hoses, and family.

Nigel Calder's, "Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual." An indispensable tome found in panic-stricken cockpits the world over.

It does not, unfortunately, come with the large, friendly letters “DON’T PANIC” on the cover. But it absolutely should.

This is not that book. We’re not diving deep here, and you’re not about to become a marine engineer. Think of this as a shallow paddle through the murky world of boat systems. Just enough knowledge to know what that weird noise might be, or where that rapidly expanding puddle of gunk under the floorboards is coming from.

Knowing your systems means you can repair your boat with a beer can, a washing-up bottle, or a sardine tin. All of which have kept Mothership going at some point during her circumnavigation.

A beer can, a washing-up bottle, and a sardine tin have all kept Mothership going at some point during her circumnavigation. Windlass repair - Belitung, Indonesia.

So, if you want to do anything more ambitious than tootle out of the marina for a Sunday evening sundowner, grab a beer and let’s dive in. But keep that empty can.

You might need it later.

1. The Engine: Your Noisy Best Friend

Yes, it’s a sailboat. But unless you plan on drifting sideways into every anchorage or tacking through uncharted reefs in pirate-infested waters, you’ll need your engine. Most rescue call-outs are due to engine failure. Don’t be one of them.

Most cruising boats have a small diesel engine, usually between 20 and 80 horsepower. It’s typically tucked under the companionway steps, inside a soundproofed box to muffle the noise. This engine is your lifeline when there’s no wind, when navigating tight spaces, or when your batteries are low.

WOBBLE Engine checks on a 75hp, Volvo Penta TMD 22: Water. Oil. Belt. Bilges. Leaks. Exhaust. Everywhere we've ever been!

Every engine comes with a user manual. Find it. Read it. It tells you what to check, what to top up, and what to replace. It also helps you understand warning lights and avoid expensive breakdowns.

Next, join an online user group for your specific engine model. They’re full of troubleshooting tips and real-world fixes for the exact weird rattle you’re hearing. It’s the cheapest mechanic training you’ll ever get and at the risk of repeating myself, Youtube is your friend.

The raw water impeller (that rubber spinny thing) loves to disintegrate offshore. Learn to change it blindfolded. Cairns, Australia.

Things to know:

Diesel engines need regular servicing. Usually around 100–200 hours.

Daily WOBBLE checks will flag up trouble. Water (coolant). Oil. Belt. Bilges. Leaks. Exhaust.

The raw water impeller (that rubber spinny thing) loves to disintegrate offshore. Learn to change it blindfolded.

Coolant is not just water. Top it up, flush it, and respect the mix or your engine will overheat like a menopausal dragon.

Fuel tanks can be horror stories waiting to happen. Learn to change filters. Carry spares.

2. Electrics: You-Know-Watts

You can’t see it, barely understand it, and curse it regularly. But modern boats run on electricity, so at least learn the basics.

Just a quick heads up. Electrics (what we’re talking about here) refers to the boat’s power systems; batteries, wiring, lights, pumps, solar panels, alternators. Basically, anything that moves or distributes electricity.

Electronics on the other hand, covers gadgets and devices that use that electricity. For example, chartplotters, AIS, GPS, radar, depth sounders, autopilot brains, and so on.

In short: electrics keep the lights on, electronics tell you where you are (and what you're about to hit).

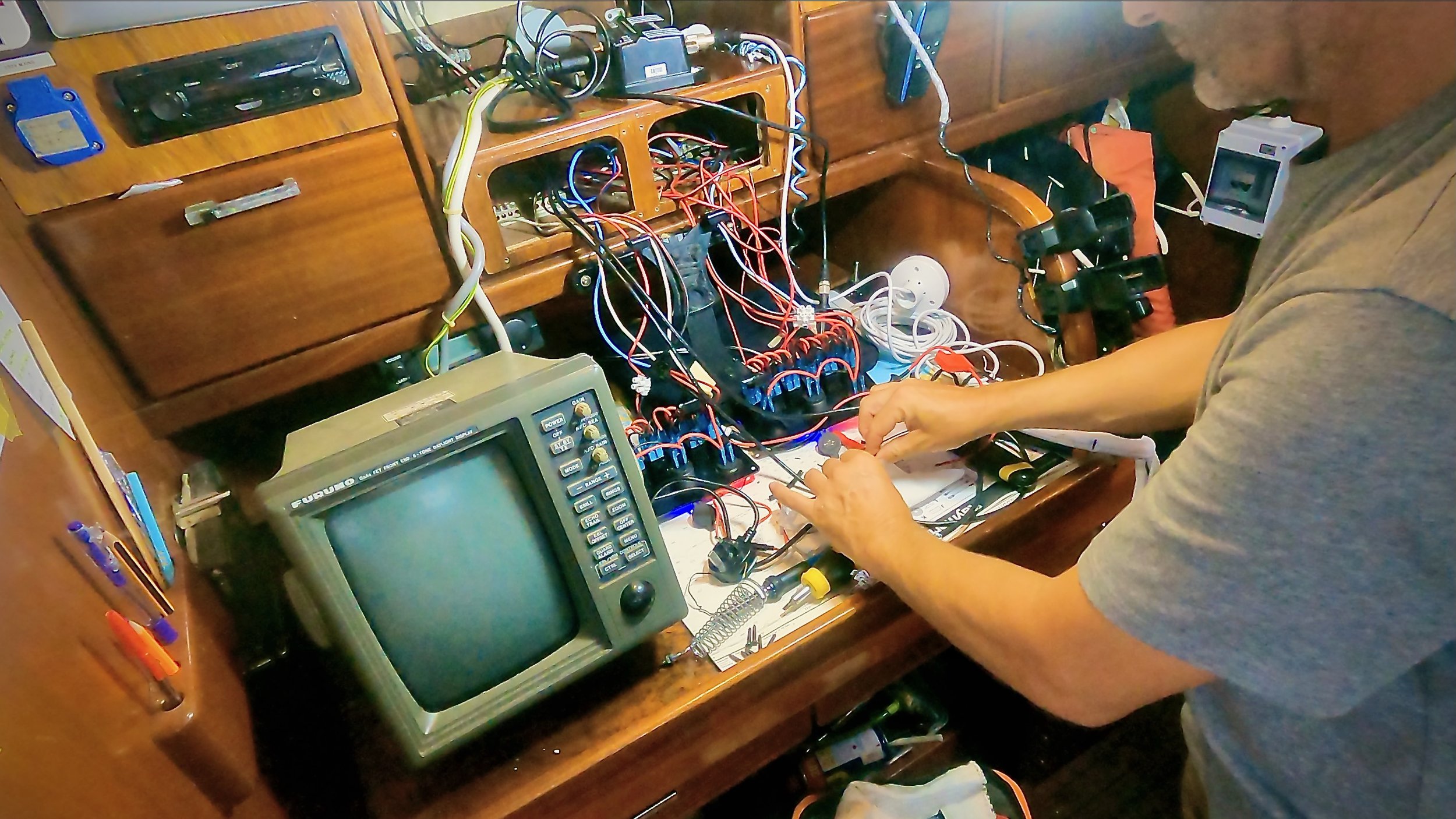

Woody installing an AIS, where electrics meet electronics on the switch panel at the chart table. Santa Cruz, Galapagos Islands.

To confuse matters even further, your boat has two electrical systems. DC (direct current) comes from batteries. It powers lights, pumps, fridges and other electronics. It’s low voltage (12V or 24V), safe to touch, and essential for boating life.

AC (alternating current) is used for household things like toasters, TV’s and computers and comes from shore power or a generator. It’s high voltage 240V or 110V, not safe to touch and too much for your batteries to handle directly.

Why two systems? Because some things can only run on DC, and others only work properly on AC. You can convert low voltage DC battery power to high voltage AC household power via an inverter. However, you need a generous amount of battery power to do this. This requires a reliable charging system or your batteries will have quick and silent death while you’re binging on Netflix.

With the recent advances in LiFePO4 (Lithium) battery and solar panel technology, boats can increasingly rely on inverters to run their AC systems.

Woody installing new Battleborn, LiFePO4 (Lithium) Batteries onboard Mothership. Red Frog Island, Bocus Del Toro, Panama

Things to know:

Most electrical problems are connection-related.

Other electrical problems are fuse related.

Get a multimeter. Learn to use it. It’s your magic wand of power.

Label all wires and fuses and carry spares

Monitor all charging sources. Never rely on just one source.

3. Water Systems: Water In, Water Out

Water aboard isn’t as simple as turning on a tap. It's a fragile mix of plumbing and pressure. We lost two tank loads during our circumnavigation. One vanished through a burst pipe behind a hidden panel, another through a rusty hose clip in the engine bay.

Your fresh water comes from tanks, usually made of plastic or stainless steel. An electric pump pressurises the system and sends water to sinks, showers, and maybe a heater. These tanks are your only supply, so every drop counts.

It’s a closed system, so any leaks, blockages, or pump failures mean you’re suddenly back to bucket and sponge baths. Keeping it working means checking pipes, cleaning tank filters, and not ignoring strange noises when the pump kicks in. Cruiser are peculiarly attuned to their water pump noises like a sixth sense.

Woody removing the Quick boiler b3 water heater for servicing. Whangarei, New Zealand.

Things to know:

A constantly running pump means a dry tank or leak. Probably in your dry food locker.

Hot water usually comes from a calorifier heated by the engine or shore power.

Mould grows in tanks. Clean or bleach them regularly.

Off-grid? Get a water maker.

Saving water is better than sourcing or making it. Rain water is delivered free to your boat.

4. Toilets (Heads): Your Personal Game of Thrones

Marine heads can be evil. Especially in the tropics. My marine toilet blog is still the most viewed video on my Mothership Maintenance, YouTube Channel. That tells you everything.

Boat toilets are either hand-pumped or electric. They use seawater (not fresh) and either discharge overboard or into a holding tank.

Using one takes technique. Especially the manual kind. Forget a step and you’ll know about it immediately.

My marine toilet blog is still the most viewed video on my Mothership Maintenance, YouTube Channel. That tells you everything.

Things to know:

They easily block. Only human waste allowed. Toilet paper goes in a bin. Yes, really.

Lubricate your seacocks. Season the pan like a salad. With oil and vinegar. Yes, again, really.

Holding tanks are small and need emptying. Regularly. Either at a pump-out station or offshore. Fish love it. Yes… etc.

Hoses calcify and need proper cleaning or replacing every few years.

Gurgling, stiff or squeaky pumps mean trouble.

5. The Gas Gourmet: Cook Like No One’s Rolling

You want hot food without exploding. It’s possible, but only with care. With improvements in solar and lithium batteries, many modern boats are switching away from gas to electric but most older boat kitchens (galleys) still use gas for cooking. So here it is.

Gas systems use bottled propane or butane stored in vented lockers. Gas travels through pipes to a gimballed cooker (meaning it swings to stay level when the boat moves). There’s usually a shut-off valve which should be turned off when not in use.

There are no international standards for gas bottles and regulations vary wildly, so sourcing gas can be extremely frustrating around the world. Looking at you Tahiti!

Cooking with gas on a moving boat takes practice and caution. Things slide, pans tip, and burns happen fast. But once you’ve got the hang of it, you’ll be the most popular member of the crew.

Irenka preparing to take butane, European Campinggaz bottles ashore for re-filling. Elounda, Crete - Greece.

Things to know:

Always use the solenoid or manual shut-off.

Test for leaks with soapy water, never a lighter. Who does that?!

Check hose expiry dates.

Fit a gas alarm. It will scream at fly spray and other aerosols, but it could save your life.

6. The Rig: Sails, Lines, and Stainless Wire

Standing rigging is the set of strong steel wires (or rods) that keep the mast upright, like the bones of a tent. Running rigging is all the ropes (halyards, sheets, reefing lines) that raise, lower, and trim the sails while you're sailing.

And by the way, they’re called "lines," not "ropes" so you get to feel clever at the yacht club. But if the mast falls, no one cares what you call them.

Depending on your setup, the sails might be rolled up neatly (furling), tied down on the boom (flaking), or stuffed into a bag. Every boat’s rigging layout is slightly different, and it pays to learn yours before things get windy.

Check regularly. Rust, frays, or "temporary" fixes are bad signs. Failures cost masts.

Woody preparing to go up the mast to do a rig check. Sawakin, North Sudan

Things to know:

Replace standing rigging every 10–15 years. Sooner if your insurer says so.

Watch for cracked fittings and broken strands.

Winches need grease. Lines need washing.

If a halyard jams, someone goes up the mast. You, probably.

Your mast looks better upright, so budget for rig checks.

7. Bilge and Pumps: Where Water Goes to Die

Water always finds a way in. Make sure it has a way out.

The bilge is the low point of the boat, hidden under the floorboards. A dry bilge is a happy bilge but water can collect there. That’s why you’ve got two pumps: one electric with a float switch that turns on automatically when the water level rises. And one manual for when things go pear shaped. The electric pump handles day-to-day drips. The manual is for emergencies. Test both.

Woody replacing hoses on electronic and manual bilge pump. Rebak Island, Malaysia.

Things to know:

Float switches fail. Either stuck on (drains battery) or off (sinks boat).

Manual pumps seize when ignored. Check them occasionally

Salty water isn’t normal. Investigate.

Keep the bilge clean and clutter free. It’s easier to spot problems that way.

8. Steering, Autopilot and Rudder: Pointing the Boat in the Right Direction

Our steering rack failed in the Maldives just before entering the Red Sea. The thought of losing steering in the Red Sea still gives us night terrors.

The wheel connects to the rudder (which turns the boat) via cables, rods or hydraulic lines. Simple when it works. Terrifying when it doesn’t.

Woody fixing the steering rack before entering the Red Sea. Uligan, Maldives.

Your emergency tiller is a backup steering bar that attaches directly to the rudder stock. It’s usually stored in some dark locker, never tested, and just awkward enough to make you hope you never need it in a hurry. But practice with it anyway.

Just trust me on this.

You’ll likely also have an autopilot—a clever electric motor that steers for you while you’re off doing something useful, like making tea. They’re brilliant, until they’re not. When they fail (and they do), you’ll be hand-steering for hours, possibly days, often in bad weather. Have a backup plan. We lost ours off the pirate-infested coast of Venezuela. It wasn’t pleasant.

Windvanes, on the other hand, are elegant mechanical contraptions that steer using the wind itself. No electricity, no fuss. Once set up properly, they’ll steer all day without complaint. They take time to learn, but on long passages, they’re your best crewmate. Unless it’s downwind. Then they sulk.

Woody steering with the emergency tiller after a steering rack failure. Uligan, Maldives.

Things to know:

Cables stretch. Rudder bearings wear. Autopilots die mid-sandwich.

Listen for groans and creaks. They're rarely good news.

Try fitting your emergency tiller before you're in a storm.

Lubricate everything. Once a year, minimum.

Windvanes need tuning, but never need charging. Learn to love them.

Always have a steering backup. Bonus points if it doesn’t involve a frying pan handle.

9. Ground Tackle: Your Seabed Hook

Your anchor isn’t ornamental. It’s the only thing keeping your boat put when you're not sailing.

Ground tackle includes an anchor (preferably a reliable one like a Rocna or Mantus), a big pile of chain (not rope - chain), and an electric windlass to lift the whole lot without breaking your back.

The anchor holds you in place. The chain adds weight and grip. The windlass does the heavy lifting. Add a snubber (a stretchy rope that takes the strain off the chain) and your nights will be much quieter, with fewer anchor-drag nightmares.

Skimp on ground tackle, and you’re gambling with your entire lifestyle.

Woody fixing the Lofran Tigress windlass - the motor and winch that lifts the anchor. Kuah, Langkawi - Malaysia

Things to know:

The windlass draws big amps and eats batteries.

Mark your chain. Guessing is not good enough.

Anchor lockers ferment. Clean them before they grow teeth.

Use a snubber. Or listen to the gearbox crunch apart at 3am, like we did during our first real storm.

That’s Boats Folks

Many years ago, after our first season as live-aboards, Mothership limped into a marina with a repairs list as long as your arm. We stumbled into the dockside potluck with our pitiful pasta offering, looking wide-eyed, weather-beaten, and in search of a sympathetic ear. What we received was a collective shrug and a sigh.

“Yes,” they said, “that’s boats.”

If you haven’t got chiropractor on quick dial, a tear-soaked engine, and a vocabulary full of expletives after your first season, you’re not doing it right.

If you can learn to love fixing boats in exotic locations, you’ve officially made it onto Team Cruiser. Turtle Bay, Raja Ampat, Indonesia

Assume everything will break at the worst moment, and you’ll be pleasantly surprised when it doesn’t. But it probably will. Because the truth is, your dreamboat isn’t just a viewing platform for dolphins and sunsets. It’s a living, breathing dysfunctional member of the family.

If you can learn to love the smell of epoxy in your hair, diesel in your bedsheets, and the joy of fixing things in exotic locations with objects scavenged from the recycling bin, then congratulations.

You’ve officially made it onto Team Cruiser.

If you want more straight-talking tales from life afloat, and information about sailboat systems and how they break, then you’ll love our upcoming book. We're inviting early readers to join the pre-launch crew and get behind-the-scenes access as we wrestle it into shape. It’s honest, unfiltered, and occasionally useful. Sign up here to get involved, give feedback, and be part of something that’ll either be a bestseller or a brilliant cautionary tale.